Flatbreads are a staple of the Indian subcontinent (India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh), with roti and naan being two of the most popular varieties (the other two include chapati and paratha, but they’re also special forms of roti. So, we can say that there are only two types of Indian flatbreads: roti and naan.) But roti is more prevalent in India and Pakistan than naan, especially in family meals. You can’t even think of a typical Indian dinner without roti.

Due to hailing from the same region, the two flatbreads share more similarities than differences. However, they have many subtle but essential differences in taste, texture, ingredients, and cooking methods. We’ll pinpoint each flatbread’s unique, defining characteristics and explore their differences to help you understand them better.

Ingredients

Roti, aka chapati or phulka, is a simple unleavened flatbread made with whole wheat flour, water, and sometimes a little salt. The dough is kneaded and allowed to rest before being rolled out into thin, round discs.

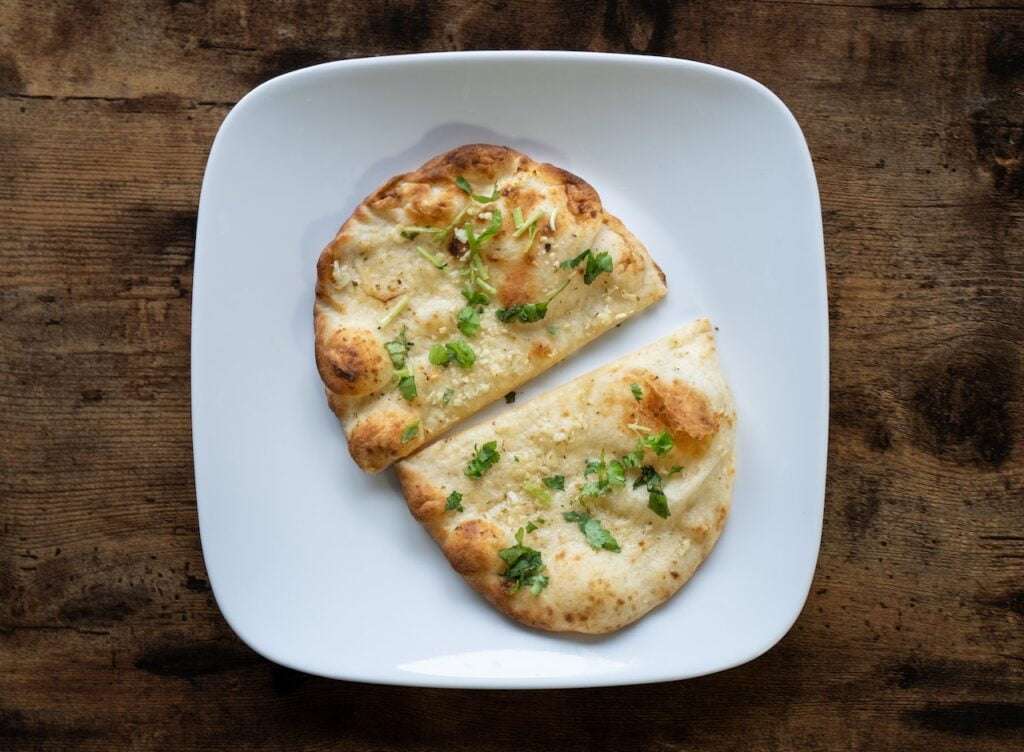

Naan, conversely, is a leavened flatbread (made with yeast or another raising agent) that requires yeast or another leavening agent, such as baking soda or baking powder. It is traditionally made with all-purpose flour, though modern versions include whole wheat flour. The dough often contains milk, yogurt, or both, which adds richness and softness to the final product. Also, naan may be flavored with garlic, cilantro, nigella seeds, and many other ingredients.

Preparation

The preparation of roti and naan also differs significantly. Roti dough is rolled out into thin discs and cooked on a hot griddle called a tava or directly over an open flame, which causes the flatbread to puff up. It is then quickly transferred to a serving dish to prevent it from becoming too crispy or overcooked.

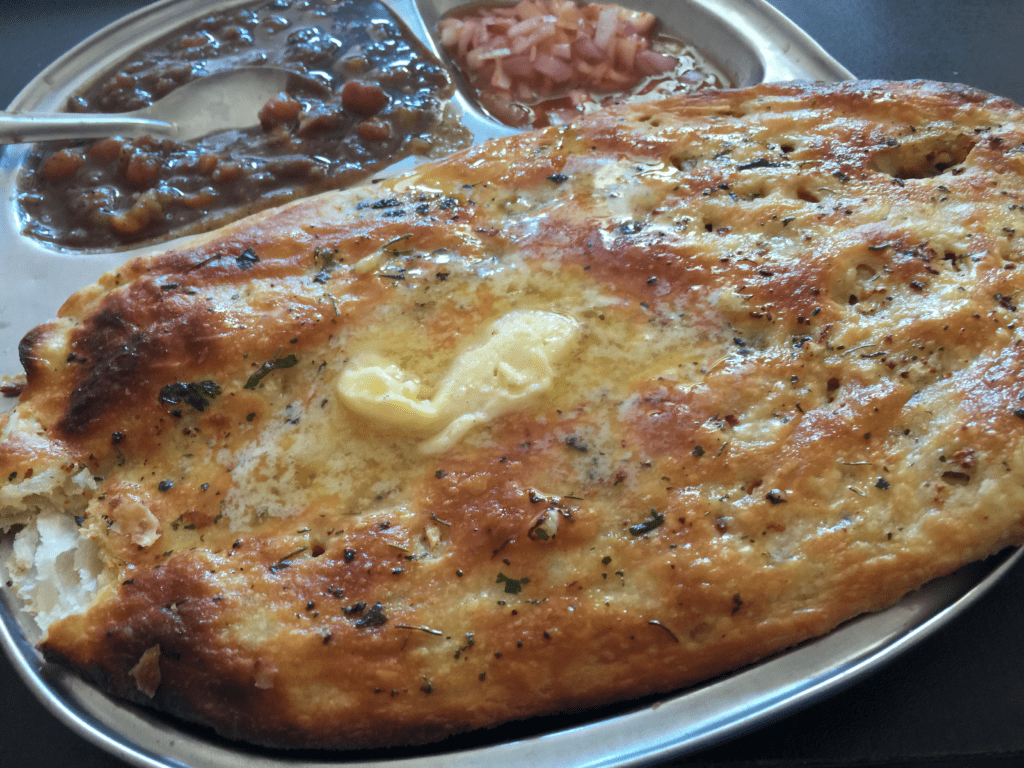

Naan dough, in contrast, is allowed to rise and ferment for several hours, which gives the bread its characteristic fluffy and airy texture. It is then rolled out into thicker, oval-shaped discs and traditionally baked in a tandoor, a cylindrical clay oven. The intense heat of the tandoor produces the signature charred spots and bubbly texture associated with naan. Though less common, naan can also be cooked on a stovetop griddle or in a home oven.

Prevalence

Naan is more commonly associated with restaurant dining. It’s always made by a professional in a special setting, which is never at home.

Due to ease of preparation, roti is a staple in Indian households, food streets, and restaurants alike, unlike naan, which is more commonly associated with restaurant dining because it requires several hours of fermenting and a large oven for cooking (tandoor).

Taste and Texture

Roti is a thin, soft, and pliable bread with a mild, slightly nutty flavor. It is typically used to accompany Indian dishes, especially curries, because it can be torn or folded to scoop up food. When cooked properly, it has a light and airy texture, making it easy to digest.

Naan, a leavened bread, has a more substantial, chewy texture and a slightly tangy flavor due to fermentation. Using milk, yogurt, or other dairy products in the dough also gives naan a richer taste. The crisp, charred edges and soft, pillowy interior make it popular for dipping into flavorful sauces and gravies.

Variations

Roti and naan both have numerous regional and creative variations. For example, roti can be stuffed with various fillings such as spiced potatoes, paneer, or lentils, creating dishes like aloo paratha, paneer paratha, or dal paratha. Similarly, naan can be stuffed with ingredients like spiced minced meat or paneer, resulting in keema naan or paneer naan.

Some particular forms of naan include additional ingredients, such as herbs and nuts, like almonds, which are usually grounded. These forms are pricier than regular naan.

Kulcha is another variety of naan popular in India and Pakistan. It’s made with maida (a more refined wheat flour.)